- Cronología

- Ca. 1820 - 1823

- Dimensiones

- 179 x 220 mm

- Técnica y soporte

- Aguafuerte, aguatinta bruñida, punta seca, buril y bruñidor

- Reconocimiento de la autoría de Goya

- Undisputed work

- Ficha: realización/revisión

- 22 Dec 2010 / 24 May 2023

- Inventario

- 225

See Sad forebodings of what is to come.

The title of the print was handwritten by Goya on the first and only series known to us at the time of its production, which the painter gave to his friend Agustín Ceán Bermúdez. Thus the title was subsequently engraved on the plate without any modification from Ceán Bermúdez's copy for the first edition of Disasters of war published by the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in Madrid in 1863.

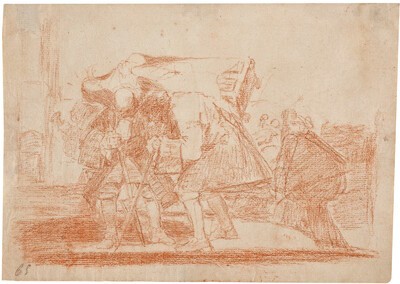

A preparatory drawing is kept in the Prado Museum.

Several well-dressed figures, probably members of the nobility, carry an image of the Virgin on their shoulders. Behind them is a group of people carrying another religious image. Jesusa Vega has interpreted this to be the Virgin of Solitude, to whom Ferdinand VII entrusted himself, asking her to preserve his health, and the Virgin of Atocha, in whose hands the monarch had left the country when he left the throne in 1808.

In order to be able to read this print properly, it is also necessary to analyse the one that precedes it, No. 66, Strange Devotion. Both the titles and the composition used link the two prints and suggest an analogous relationship between them. The two prints show a sacred image being carried in the first case by a donkey, and in the second by a group of members of the aristocracy.

Nigel Glendinning suggests that the source of inspiration for engraving no. 66 may be the fables of Félix María Samaniego (Laguardia, Álava, 1745-1801) and José Agustín Ibáñez de la Rentería (Bilbao, 1751-Lequeitio, 1826). Engraving no. 66 reproduces the first part of them, in which the image is described. The second part, the moralising part, could be the one condensed in print no. 67, the one we are dealing with here.

If we compare this engraving with the previous one, we come to the conclusion that it is quite likely that the criticism is focused on the social class, well characterised by its somewhat old-fashioned clothing as Glendinning has noted, rather than on the circumstance that unfolds before our eyes. In this way, Goya would be questioning the aristocracy that revitalised this type of belief after the War of Independence, even when a certain sector of the Church itself questioned it.

The plate is in the National Chalcography (cat. 318).

-

Francisco Goya. Sein leben im spiegel der graphik. Fuendetodos 1746-1828 Bordeaux. 1746-1996Galerie KornfeldBern1996from November 21st 1996 to January 1997cat. 157

-

Francisco Goya. Capricci, follie e disastri della guerraSan Donato Milanese2000Opere grafiche della Fondazione Antonio Mazzottacat. 147

-

Goya et la modernitéPinacothèque de ParisParís2013from October 11st 2013 to March 16th 2014cat. 106

-

Goya, grabadorMadridBlass S.A.1918cat. 169

-

El asno cargado de reliquias en Los desastres de la guerra de GoyaArchivo español de arte1962pp. 221-230

-

Goya engravings and lithographs, vol. I y II.OxfordBruno Cassirer1964cat. 187

-

Vie et ouvre de Francisco de GoyaParísOffice du livre1970cat. 1108

-

A solution to the enigma of Goya’s emphatic caprices nº 65-80 of The Disasters of WarApollo1978pp.186-191

-

Fuentes emblemáticas del asno cargado de reliquias de la serie Los desastres de la guerra de Goya1982Goya1982pp.274-278

-

Catálogo de las estampas de Goya en la Biblioteca NacionalMadridMinisterio de Educación y Cultura, Biblioteca Nacional1996cat. 283

-

ParísPinacoteca de París2013p. 153

-

Goya. In the Norton Simon MuseumPasadenaNorton Simon Museum2016pp. 114-151